I know what you’re thinking. What is “dynamic bulkification”? Is it some new terms that I’ve just made up to represent some wild new Apex design pattern?

Yep, that’s about right.

I discuss this in my April appearance in Salesforce Apex hours – you can watch the full video here:

Or, you can read about it in this article below.

Let’s Talk About Integrations

As an ISV partner, I see a lot of orgs. Many of them have integrations with outside services that use APIs to insert and update Salesforce records. Historically, integrations have used the SOAP API, though recently more of them are using the REST API.

The SOAP API is not an easy one to use. It uses XML as the data format and is programmatically rather complex. The REST API is much simpler and uses the common JSON format. So it makes sense that new integrations are using REST and older ones gradually migrating to it. However, the SOAP API does have one advantage over REST – all of the Salesforce SOAP API commands use arrays for transferring record information. In other words, bulk operations are just as easy as individual record operations. So integrations using SOAP would typically perform bulk operations.

You can perform bulk operations with the REST API – they are called composite operations, but they are more complex than the default single record operations. The documentation covers them almost as an afterthought. As a result, anyone learning how to use the Salesforce REST API will inevitably learn the single object patterns first, and may never even notice the composite patterns. Indeed, if you don’t read the documentation carefully, you might conclude that the single object patterns represent best practices.

As a result, we’re seeing more and more orgs that are experiencing a very high frequency of single record operations from integrations. This is not a good thing.

High Frequency Record Operations

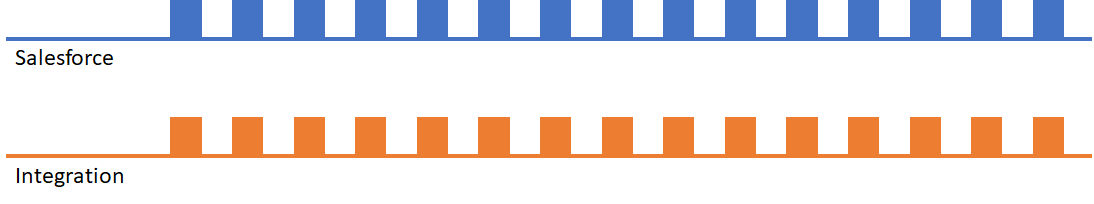

Consider a relatively simple org – one with few triggers and little automation, that is experiencing a high frequency of single record operations. Each incoming API call results in an operation in Salesforce, but as long as the Salesforce processing time is short, you’re unlikely to see any problems.

It’s also unlikely that the company building the integration will see any problems, because this is very likely to be the scenario they test for.

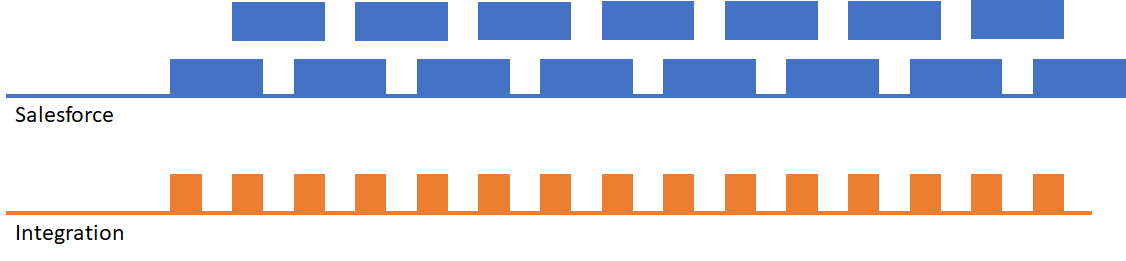

But what happens when you start adding additional functionality to the record processing in the form of Apex triggers and automation? The processing time for each request will inevitably increase resulting in the following scenario:

As you can see, Salesforce will still be processing one request when another comes in. However, this may not be a problem, as the different triggers will run in different threads – in parallel. So everything is fine unless…

High Frequency Record Operations with Locking

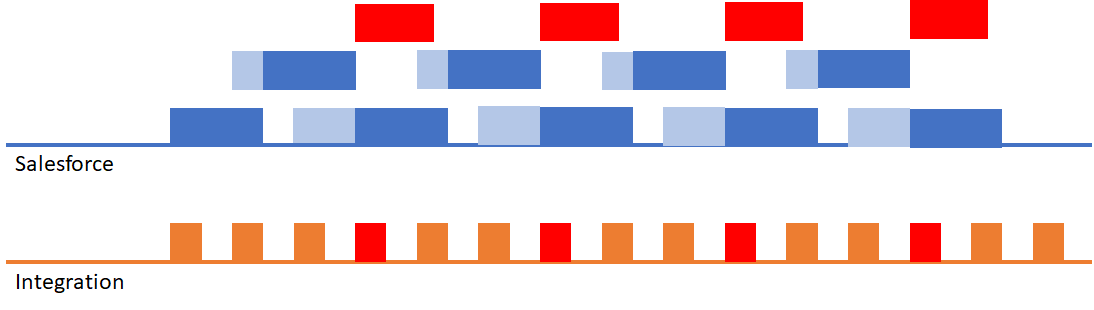

What happens if the API request and corresponding Apex and automation causes a record lock? This can happen when trying to insert or update records that reference a common object. For example: if you tried to update multiple contacts on the same account. The one we see most often is that of a marketing or sales automation system that is trying to insert multiple CampaignMember records on the same campaign – each individual insertion creates a lock on that campaign.

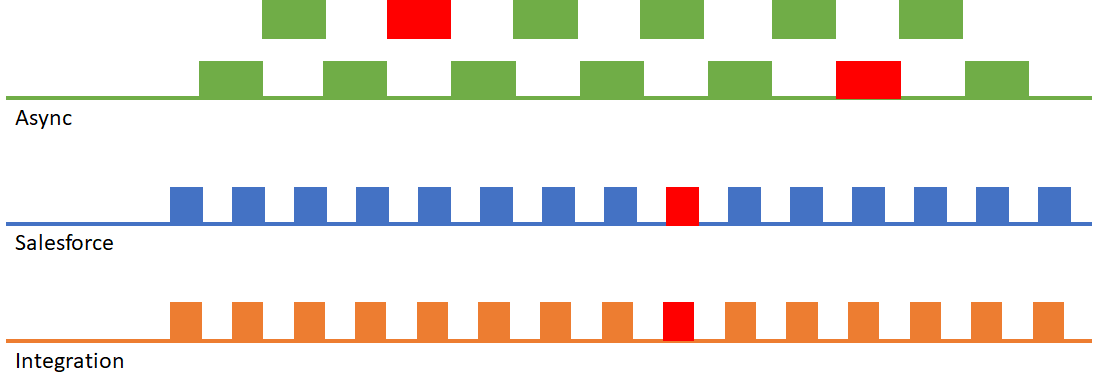

This results in the following scenario (where a red block indicates a locking error):

In this scenario you’ll starting seeing API failures on the integration due to record lock errors.

How can you address this scenario?

You could ask the integration vendor to stop performing individual record operations and bulkify their integration. That’s the right solution, but good luck convincing them to do so. No, in the real world it’s up to you to resolve this.

The obvious first solution would be to reduce the processing time for those individual record operations. You’re probably already familiar with the best ways to do this:

- Dump Process Builder (Use flows or Apex – process builder is horrifically inefficient)

- Prevent reentrancy (triggers that invoke automation that invoke triggers and so on)

Another common approach is to move part of the processing into an asynchronous context, typically a Queueable operation.

High Frequency Record Operations with Asynchronous Processing

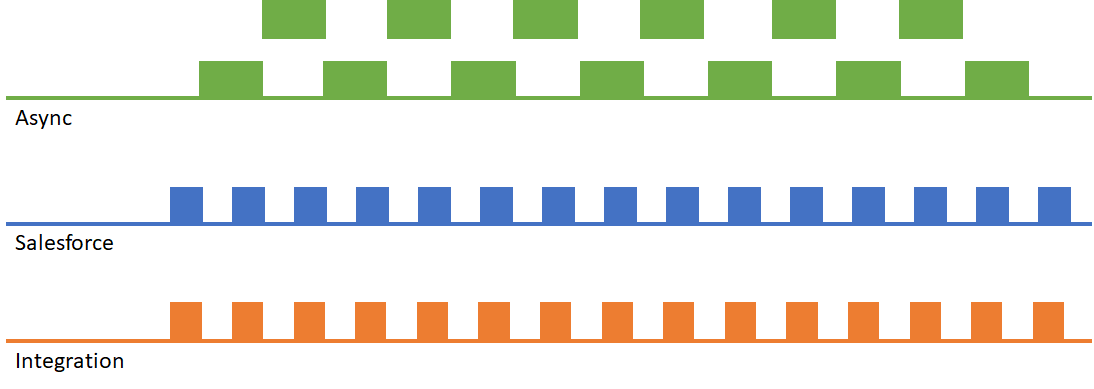

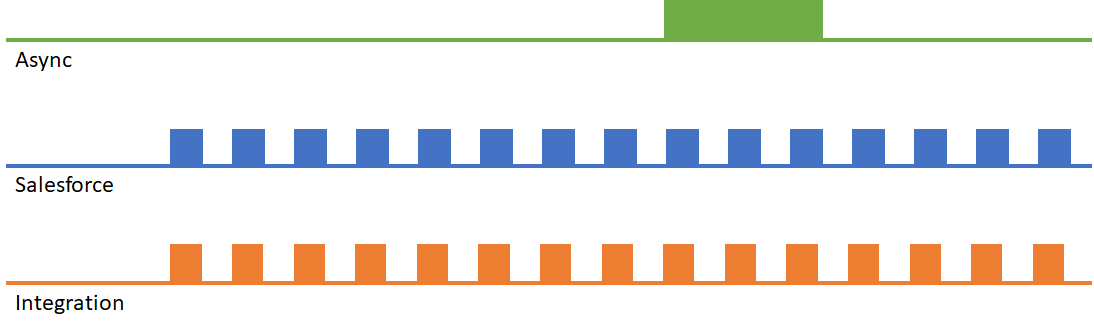

Moving part of your processing into an asynchronous context results in the following scenario:

This approach also results in a very high number of asynchronous operations, which can be a problem on larger orgs that are already nearing their 24-hour asynchronous operation limit.

Dynamic Bulkification to the Rescue!

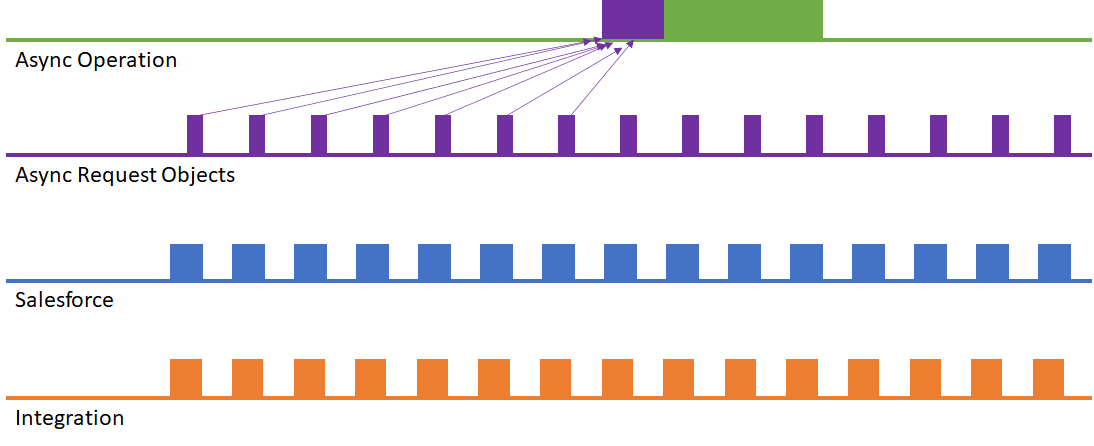

Which brings us to the design pattern that led me to introduce the term “dynamic bulkification”. The idea here is simple – translate large numbers of individual record operations into a single bulk operation as shown here:

This approach is a fantastic solution to the problem. That’s because Salesforce is optimized for bulk operations – in most cases the time to perform a bulk operation is far less than the sum of the times of the individual operations. This also results in considerably fewer asynchronous requests, depending on how many single requests can be combined into one.

The question then becomes – how does one implement this?

One approach is to use platform events.

Platform events are self-bulkifying. That is to say, while you may publish individual events, your platform event triggers will always receive groups of events.

While this may seem the ideal solution, there are some problems with this approach:

- Platform events are not 100% reliable. Event publishing can fail, and even events that are successfully queued may fail to publish or be delivered.

- If your asynchronous operation is inefficient (unbulkified, or performs DML operations that invoke process builder), you won’t gain the full benefits of the bulkification.

- Platform events currently run with synchronous context limits (which are lower than the asynchronous context limits).

- Platform events are not ISV friendly – there are challenges with incorporating them into packages (platform event limits and quotas are common to the org and packages).

I won’t say that you shouldn’t use platform events for dynamic bulkification. They are probably good enough for most scenarios. But if reliability is a priority, or you are building for an ISV package, they are probably not the right approach at this time.

Dynamic Bulkification with an Asynchronous Framework

A more reliable approach is to build on an asynchronous processing framework. Such a framework uses a custom object – call it an async request object – to represent async requests to be processed. I won’t go into detail on how these frameworks operate, or all of the advantages of taking this approach. You can read all about it in chapter 7 of my book “Advanced Apex Programming”, where I discuss this approach in depth.

What I don’t discuss in the book is the possibility of merging async request records of the same type in order to perform dynamic bulkification. This results in the scenario shown here:

This approach has many advantages

- No possibility of data loss – failing operations are marked on the async request object where they can be tracked or retried.

- Always runs in asynchronous context limits

- You can support different types of async operations with a single custom object

One final comment. This approach is not theoretical. It’s the one we use at Full Circle Insights in our own applications, and we’ve been gradually adding logic to merge different types of async requests as we’ve seen more of our customers run into ill-behaved integrations.

This does not consider API limits. In many real world scale implementations API limits will force the external invocations to be bulkified off-platform.

The assumption that the external integration is inherently multi-threaded or that the record processing in triggers/automation is async also looks wrong to me. Any external system using fire-and-forget either assumes the target app will asynchronously respond in failure cases or is a broken approach. In addition, it is highly likely the external system will want to guarantee processing order is maintained especially when there are multiple updates to the same (or related) records.

I’d suggest you read the article more carefully.

I made it very clear that this absolutely should be dealt with by the integration! This approach is what you use in cases where the external integration is ill-behaved.

As for the external integration being asynchronous. This is true, and it reflects what we have seen in the real world.

Consider an external marketing automation tool. It will, indeed, want to be synchronous in the processing of a given lead. However, leads come into these systems asynchronously, and we definitely see them being processed that way – the problem occurs when these operations on different records are locking a common record on Salesforce. This is not a factor that external systems seem to take into consideration.

I did read your article carefully and noted that comment. I believe my points still stand and what I am pointing out is that you failed to mention these aspects directly.

Now, I understand you are reacting to a real world scenario, but you did not outline what it was before diving in.

The failure to explicitly mention API limits is problematic because others may decide to follow this on-platform route and waste significant effort creating their own framework instead to selecting an alternative (which could be to switch to a different integrator or to intercede with some middleware). They could easily have quite different volumes of updates flowing in compared to your case.

That the “integration” runs async is a key point (and one I would say is vital to understand before reading the bulk of this explanation). Much of what you work around is entirely irrelevant when the external system performs synchronous processing that guarantees data integrity (here you are effectively looking at the equivalent of a distributed data transaction).

You should also address sequencing and error handling aspects of such an integration scenario. I can imagine that your bulkification could easily misbehave and produce incorrect results.

For example, an object used in the integration has a state indicator and a lifecycle. This lifecycle allows certain fields to be changed in different states but not others and has strict sequencing of the state. Let’s say state 0 can transition to state 1 and fields A and B can be changed in this state. State 1 can be transitioned to state 2 and fields B and C can be changed. Now the external system validly updates a record of this object from state 0 to state 1 and changes field A (permitted) and shortly thereafter updates to state 2 and changes fields B and C.

How does the bulkification operate in such cases? Does it ensure the first operation is processed entirely on its own, or are they combined together? If on its own, this will work nicely but actually hasn’t bulkified the processing, at least against that given record. If the operations are merged together this will fail since it would appear the record goes directly from state 0 to state 2 while changing fields A, B and C.

Note that this sort of scenario is something we have had to deal with in real world too.

Don’t get me wrong; the info in this article is valuable, but needs to be clearer about the context where it fits and the constraints it faces. It would also be good to at least mention transaction sequencing, isolation of same-record actions and error handling to round it off.

I beg to differ.

1. The first paragraph makes it quite clear that we are an ISV partner and that this is in response to what we are seeing in customer orgs. If that’s not real-world, I don’t know what is.

2. This entire article is about how to respond to ill-behaved integrations. It is absolutely clear both at the start, and later “You could ask the integration vendor to stop performing individual record operations and bulkify their integration. That’s the right solution, but good luck convincing them to do so. No, in the real world it’s up to you to resolve this. ” that this is not a recommendation of an overall approach.

3. The total API limit issue is more theoretical than real. Here’s why: Let’s assume each operation is a DML record insert of a new customer response. The base API limit is 100,000. That would mean 100K new leads a day (true, there may be other integrations, but let’s assume this is the “bad” one). Awesome. But what kind of company actually gets 100K new leads a day? A large enterprise company. But their API limits are going to be MUCH higher. No, what kill them is actually the max # of async operations – because if you try to address this problem by using async operations on individual records, that’s 100K async opertions, and they are using async operations for a lot of other things. In dealing with this particular scenario, I have not yet seen the API limit be an issue. The problem is always short bursts of high-frequency operations – and this pattern is great at that. Finally, the total API limit is not a consequence of this solution, it’s a consequence of the ill-behaved integration – something that is stated to be something we have no control over.

4. Yes, I could have made it more clear that the incoming requests are asynchronous, but as you note, the scenario only applies in this case. I don’t know what your experience is, but we’ve found that external services are often asynchronous – they are only synchronous for individual records, not across different records. In the case of a sales automation system – individual leads come into that system asynchronously and are processed asynchronously.

5. As I mention, this discussion references an asynchronous design pattern described in my book – which does discuss error handling. Indeed, the article does mention it as well in noting this as an advantage over process builder.

6. Your note about the complexities of this bulkification approach actually apply to any use of asynchronous processing on a record, not just this design pattern. This article doesn’t try to address every possible problem with handling operations asynchronously – it’s up to users to address scenarios based on their own needs. The purpose of this article is to discuss an approach to a very real problem – not to provide a formulaic solution to every possible scenario. The question you raise are good questions that anyone adopting this idea should consider.

7. Again, I believe the context was very clear. The problem stated is that of ill-behaved integrations updating individual records at a very high rate. This is a real world problem for some people – not everyone by a long shot.

Ultimately it seems to me you interpreted this article as a recommendation for an architecture – that I’m suggesting that people create integrations or solutions that update individual records and use dynamic bulkification to deal with the issue. Nothing could be farther from the truth – I tried to make it very clear from the very beginning that integrations should always operate in bulk. In the ideal world this solution should never be needed. It is an approach intended to deal with ill-behaved integrations. Those you can’t get out of for various economic or political reasons.

I agree with some of what you say, including that you framed it as for badly behaving integrations, but disagree with others, such as that your context was clear. It is, however, clearer after this discussion.

A small point I would make is that Salesforce is not just a CRM, it is a platform, and I obviously viewed your article from a very different perspective. I guess this is why I had a very different set of concerns.

We have cases where integrations can create 10s of thousands of non-CRM records a day and where multiple updates per record can happen per day from off platform. API limits are a thing.

Not wanting to cause ill-feeling, I’ll shut up at this point.

No ill feeling. Indeed, I do appreciate this conversation – it may be as valuable or more valuable to readers than the original article. And if it got a bit heated (for which I take my share of responsibility), that’s ok – as sometimes technical conversations do when people are passionate about their opinions.

Your comments lead to some incredibly important take-aways for readers.

When reading any article (or viewing a session) it is very important for readers to pay attention to the context and to interpret it based on their own needs. There is a tendency for for content to be interpreted as “this is the newest best way to do things”. This is rarely the case. As you say, Salesforce is a platform – and as the platform has grown the level of complexity and the number of possible scenarios as grown. It is no longer possible (if it ever was) to hold on to a simple set of design patterns and best-practices, or to blindly deploy solutions from articles or forum answers that one thinks may be applicable. A developer or architect must understand the design pattern and approach and consider it in the context of a specific solution. I’ve seen people misuse content way to often.

In this particular case, the problem statement was that of rapid APIs from an ill-behaved integration performing DML operations on Salesforce objects that result in locking errors because of time consumed by Apex or automation on those objects. That’s it – the only scenario this solution addresses. There are potentially other applications for this approach, but they aren’t addressed here. Your comments help make this point – as this solution clearly is not even remotely applicable to scenarios you face. If this conversation helps readers to be skeptical and really think about their specific problems, that is a very good thing.

It is also not surprising that I rarely see scenarios where API limits are an issue. Remember, I’m an ISV partner building a native Salesforce application. We don’t make inbound API calls. And one of the nice things about API based integration limits is that it’s relatively easy to figure out which integration is consuming those calls – i.e. easy to see who to blame. Since it’s never us, we don’t get those calls.

For those readers who are building a solution that includes an integration, it is my sincere hope that they build a well-behaved one. But it’s also important to understand that “well-behaved” depends very much on which API and part of the platform is being touched! If it’s Salesforce CRM, bulkification on the integration side is essential (and I’d tend to recommend exposing a custom REST endpoint rather than using the platform API if possible, as they can build a solution that is more secure and scalable that way). If they can’t bulkify the integration, some kind of middleware solution might be a good approach, as you noted. If it’s integrating into Heroku, it may not matter at all – Heroku applications can be built to handle vast number of incoming API calls. If it’s some other cloud like Pardot (or whatever they are calling it today), I have no idea – as I haven’t researched integrations into that technology.

So thank you for engaging in this conversation – I sincerely hope that people reading the article will read through to the end.

A very interesting read. In our org, we have some integrations we rely on heavily for mission critical purposes that unfortunately considered legacy and have more than a few problematic design patterns. I absolutely feel that we as internal admins and automation designers/developers that are the ones responsible to find creative ways to mitigate the structural problems of the managed package automations, apex classes, object metadata structures, and other bits and pieces we can’t actually change.